The Cheoah is a river whose beauty and danger are inextricably intertwined.

I’ve stared down rivers before. Hollow, thousand—yard kind of gazes, checking just one more time for a line that isn’t there, one that I felt like I could live with for a moment. Maybe hoping my patient attendance might compel the river to nudge the conditions in my favor. The river stares back, without acknowledgment, long after I’ve given up and looked away. The river is always honest about its nature, and while too many times it seems as though the water is on our side, sharing the same ride, it’s merely coincidence. Even as we weave ourselves deeper into the fabric with grace and trust, there is no immunity, no loyalty reciprocated. Our familiarity, expectations, and comfort actually change nothing about the river and its potential. Callous one minute, benevolent the next - there is no pattern. There’s an asymmetry between our desire to “understand why” and the continual, indifferent hum of the universe and everything in it. We’re programmed to stare down the threat, and wait for it to look away. Yet this is rendered irrelevant under the simple response of water to gravity. As humans we’ve staked our whole strategy on “why” and “how”. But the river simply “is” - and it’s the things that “are” which can be the hardest to accept.

I haven’t always loved the Cheoah. I still remember the first actual recreational release. Logistics were a bit of a disaster, as paddlers were required to ride to and from the river in buses from Robbinsville. In the midst of the brewing gridlock, we gave up and went to the Ocoee. I took my first run on the Cheoah a while before that though. A big flood had washed out Highway 129 and we were out there the day after, with the river running around 4500 cfs. Young and enamored with a river brimful of crashing water, I paddled the lower two miles, careful to dodge the Komatsu excavator digging rocks out of the entrance to Bear Creek Falls, staying far right on the big drop, and ferrying my slicer hard left with determination through the chaos below, squeezing by a huge hole that covered most of the channel with inches to spare. Below the Tapoco Lodge we all got annihilated in successive, angry holes, before congregating below in the lake. It was a scary, yet inspiring experience.

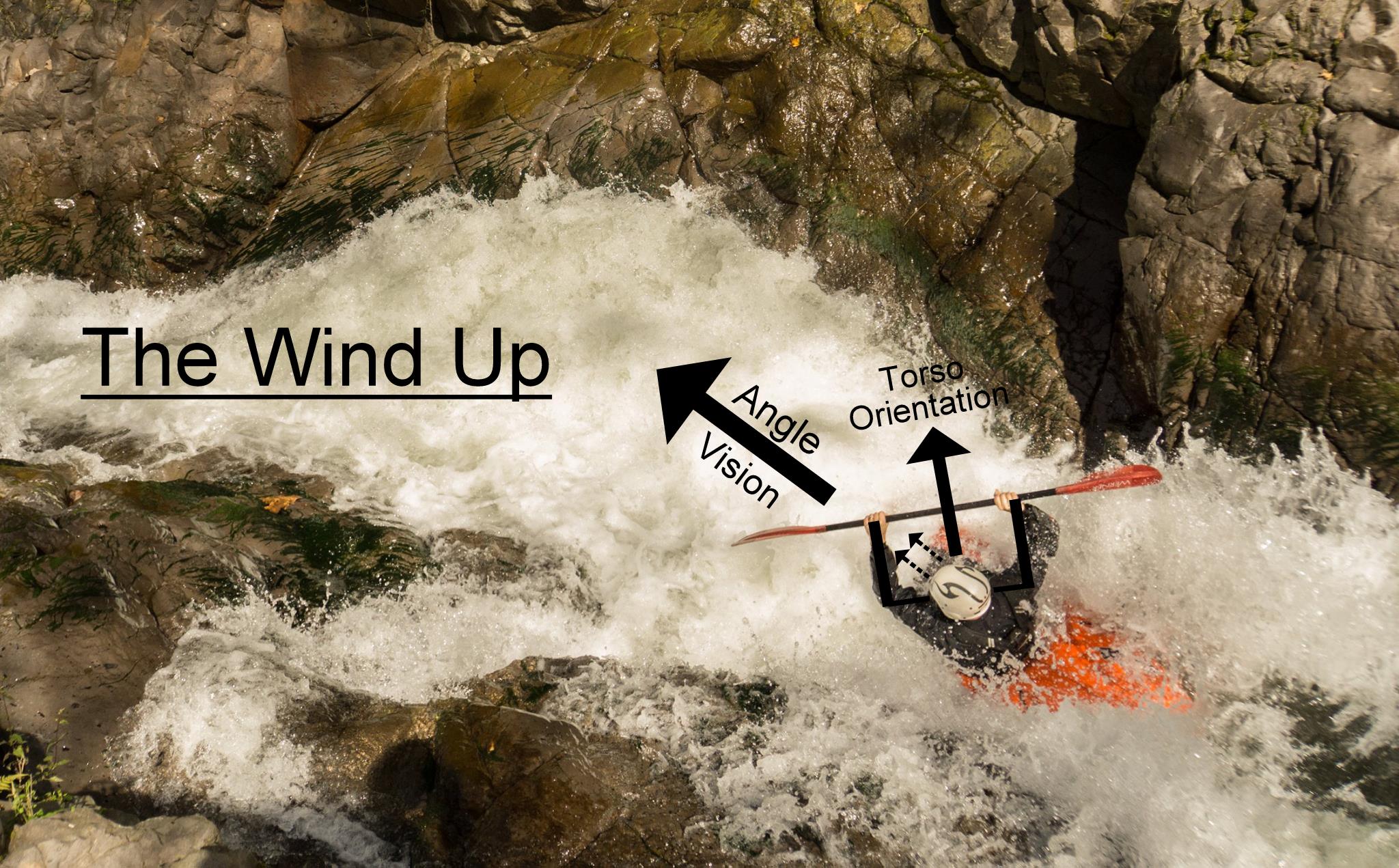

After paddling the river a few times once releases began, I didn’t quite get the thrill. I was head-over-heels into the world of steep creeking, and the Cheoah just didn’t have enough “drops”. As my skill improved though, I traveled to paddle in other locations and discovered the wide range of styles of whitewater that are available. I started to realize that the Cheoah offered a type of paddling that is hard to find in the south, and that it scratched an itch that a drainage ditch never could. I found in the Cheoah a river that not only you could water-boof to your soul’s delight, but a river you could lean into and become one with. The experience of dropping into big diagonals, using your body to break through features, and pushing through dense water with your head tucked produced a kind of soaking wet flow-state that delivered me into the lake giddy and fuzzy-headed, every time. It was pure action. One lap I was paddling so fast and getting blasted so hard in the face by the river that by the time I hit Tapoco Lodge, I had actually washed away all the tear film from my eyeballs. Floating through Yard Sale with blurred, halo vision was surreal, and I was relieved to discover that it was temporary! Leland Davis was right to compare the Cheoah to the burly, continuous rivers found in Idaho. And we were lucky as southerners to have a little taste of it so close by.

Looking down towards the bottom hole of Python, which may be much more dangerous than we realize. It’s the middle hole in the picture on the right side, just upstream of a mid-stream Sycamore Tree.

Unfortunately there are two sides to every coin, and pushy continuous whitewater is dangerous in a way many of our local creeks are not. Add in the rocky nature of Southern Appalachian rivers, and we’re left with the reality that the Cheoah is a nasty place to be out of your boat. Compounding the risk is a riverbed that was essentially dry for 80 years due to a hydro-diversion, which caused trees to grow throughout the streambed. While many work-days have been organized over the years to remove dangerous trees and stumps from the unnatural places they have resided for so long, there are still hazardous rocks and remnants of trees in the stream bed. It is these realities that have led to the current moment we are in, where since releases have began we have lost four experienced paddlers on the Cheoah, three of which in one rapid. All of these people were highly experienced veterans, and loved by so many, and it’s very difficult to lose them to a river that they and so many others love so much. I did not know any of the wonderful people who passed away on the Cheoah very well, but they were familiar faces in a tight-knit community, and I feel very much for their families, and our small little tribe of river-lovers.

So here we are. Reconciling “why” with “is” will always be painful. But we have to find a way to carry on. Some may decide the Cheoah is just not worth the risk. Others may keep doing it the way they always have, and yet many more I anticipate will try to adapt a way of moving down the river that will mitigate more of the risk. In order to move forward, we must acknowledge and accept what is, and then adapt as individuals to find a way to paddle the Cheoah as safely as possible, if at all. It’s a very personal decision how to proceed. After reading much written by the community in response to the latest drowning, I feel compelled to share my thoughts about what needs to change. I want to stress that I pass absolutely no judgement on anyone who has run the Cheoah and the style with which they have done it. Paddling style is a personal choice and I support the notion of paddling as a sport unchained by convention and externally imposed limits. With that said, I have spent many years now focused on the various methods of safely moving down dangerous rivers, and I wish to not only respond to some of the proposed solutions, but also recommend the changes that I think would be effective at reducing any future toll this great river may take on our community.

We are the solution. Our ability to adapt is our greatest strength. I have heard discussion of filling in hazardous looking voids in rocks with concrete, hiring someone to hang out with a rope, and putting up signs along the river corridor. All of this is passing the buck. If as paddlers we wish to be seen as capable, competent, self-reliant, and accountable as groups and as a community, we need to change our culture of movement down the river.

Early on my friends and I were often out paddling rivers we didn’t necessarily have the skills to complete full descents on. We had no guide, and no free advice. We had to make the right decisions every time. Even if the consequences weren’t as serious as we suspected, we had to operate under the assumption that it could get real. We just didn’t understand enough about whitewater, paddling, and reading the water to be confident. So we scouted. We portaged. We set safety. We threw ropes. If anyone was concerned about a particular spot, we worked together to create support and protection. It didn’t take more than a few years of this constant existence on the edge of our comfort zone, and the critical ingredient - prudent action, that we became confident. Often enough there was one specific rock or feature that was the problem with a section. Easy enough - set a rope, a pair of hands, and protect. But it got complicated when the water got more continuous. Scouting took longer, setting safety could be tedious and time consuming. Portaging took longer. And it was and still always is, tempting to just route it and skip all the work.

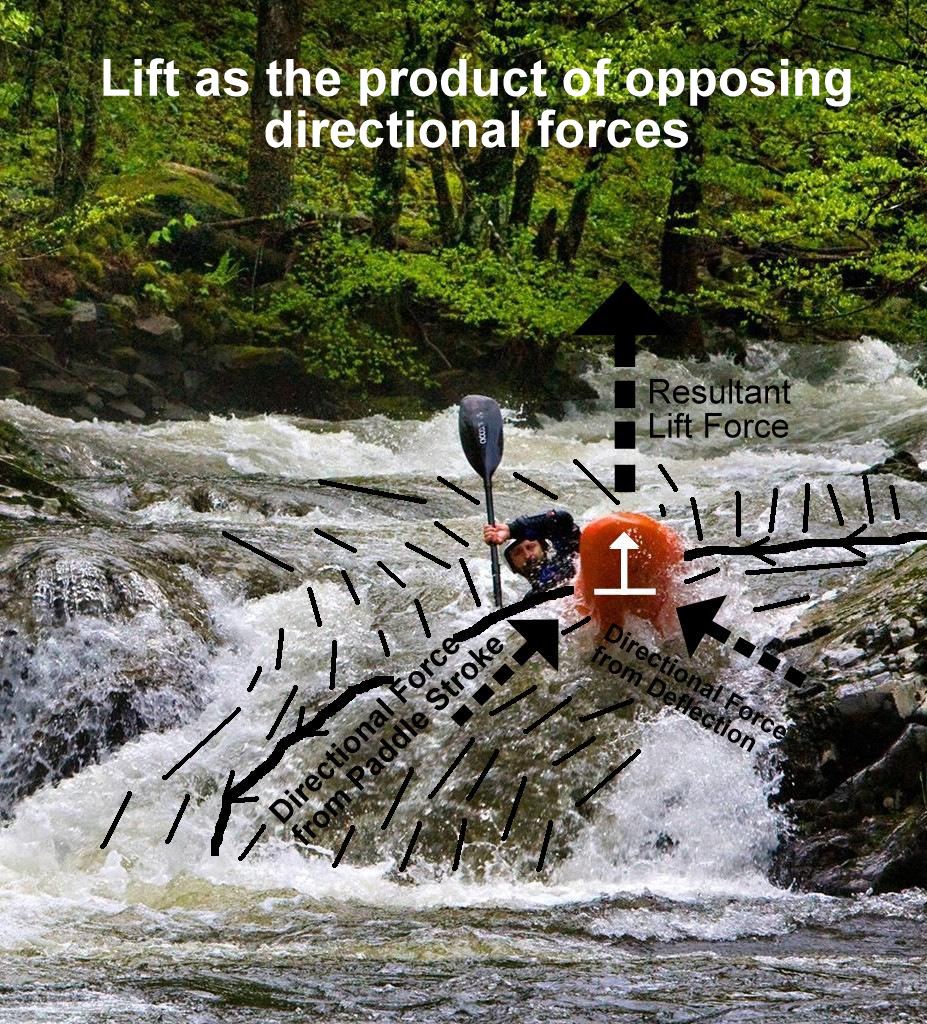

I’m seeing lots of searching after this latest accident, and much of it is the desperate hunt for a rock or tree, or static feature, that we can blame for these tragedies. It facilitates a quicker, lower-effort solution, like filling a crack with concrete, or putting up a sign. But the reality is that what makes the Cheoah so dangerous is the same thing that makes it so wonderful - it’s stacked. One drop and rapid after another with no break for hundreds of yards at a time. The river just doesn’t stop, and particularly the section from a few hundred yards above Bear Creek Falls down to several hundred yards below is essentially one single, large, pushy rapid full of drops, holes, ledges, and big waves. It’s my strong inclination to think that the fatalities that have occurred are not from rocks in the river, but the water itself. The truth is that the Cheoah exposes paddlers to a higher risk of flush-drowning than most other rivers in the region.

The solution is to slow down, eddy out, get out, scout, set safety, and portage if necessary. This is the process by which most advanced paddling trips adhere to, particularly exploratory trips. We should be doing this more on our home runs too though. Doesn’t it make sense that if there’s a risk of flushing on a long set of powerful rapids that your group would get out and set a rope? Maybe even multiple ropes?

I’m reminded very much of how rock climbing works.

Take the Grand Teton for example. Mostly just hiking/scrambling, the Grand does have 3 short sections with insane exposure and 5th class moves up to 5.4 (for the layperson, legit vertical climbing with no room for mistake). They are all back to back. If you free-solo, which scores of folks do, quite reasonably, it takes 30 minutes to work through this section. If you use protective gear and a rope to safely belay even just a two-person team through this same stretch, it will probably take two hours or more. The question for any potential climber is: How much extra time is your life worth? For the true experts, it may indeed seem rational to just climb up quickly without protective gear. The moves are pretty easy for anyone with experience, and the extra time to protect the route seems like overkill. Conversely, newer, less experienced climbers would probably do well to just bring the gear, take the extra time, and enjoy the extra layer of safety. Not only that, but they’ll learn a lot more about placing gear, cleaning, building belay stations, rappelling, and the like. Any given summit day on Grand Teton, there’s a mix of folks both free-soloing, and protecting the route. What bothers me when watching others paddle the Cheoah, is that regardless of how a group or person appears to be performing, and the level of experience, it seems like almost everyone is “free-soloing” - to borrow from the climber’s lexicon.

To be as clear as possible, we all need to look at our skill level, group, daily confidence, the water level, and all other conditions, every time we do anything, and decide what kind of protection we need. Maybe some days we’re feeling the fire and decide to rally a solo lap with no eddys. Maybe other times that’s not the call. Maybe sometimes there are externalities we aren’t even responsible for that change what the right decision is, down to the instant. We have an incredible toolkit at our disposal. I’d love to see more people scouting and setting safety everywhere on the Cheoah, but particularly in the area surrounding Bear Creek Falls. That section is just too serious to not see more folks slowing down and placing protection for their group.

Below is a diagram I’ve made of that part of the river that shows many of the primary features, lines, and potential points on the river where safety is a really good idea:

As seen above, there’s three main areas of concern: The entrance to the falls, the falls, and the rapid below. The rope stations listed are not official, or even convenient, but they are located on the map strictly on the basis of where they would be useful.

Rope Station #1 - Because swimming over the actual falls could be and has proven to be life-threatening in the past, it seems wise to have someone get out and hold rope at Rope Station #1. Then the strongest paddler can route down and act as an in-water safety boater ready to provide assistance. This greatly reduces the chances of someone swimming over the falls, which would seem certain to escalate the situation.

Rope Station #2 - Easy spot to walk down and set a rope. A 70 foot rope should reach most swimmers at the base of the falls. This is a critical spot because it keeps swimmers from flushing into the rapid below (Python), which is where 3 fatalities have occurred. A safety boater in-boat (perhaps your most competent team member) could add protection. The person holding rope above the big one at station 1 could easily hop down here for their group and cover both spots. This is a common practice on rivers all over the world. Protect, and then relocate. The logistics for maximum efficiency of course are different in each situation. The point is to be intentional and thoughtful, not impulsive and reactive.

Rope Station #3 - This spot may be difficult to get to, and may add some amount of risk to the person holding rope. I’m not sure anyone has ever held rope here, but I highly suspect that this hole is directly responsible for some drownings. One rafter drowning occurred here for certain, who was miraculously revived. The reality is that swimming into this hole, which is where all the water goes at the end of Python, is very bad news. A machete works wonders on kudzu and blackberry bushes.

A note on diagrams: Make your own. This one took me half an hour to source the satellite imagery, merge the photos, dink around with fonts and paint, etc. In fact, diagram it out on the river. You don’t even need to draw it anywhere other than your mind. It’s this way of thinking that will make the difference.

Here, two kayakers are boofing the safer side of the deadly ledge at the bottom of Python. Notice all the middle flow through the tongue goes into a vicious hydraulic that is backed up by rocks. This is a terminal hole. The options here are sneak down the other side of the island on the West Prong Line, eddy above the ledge on the left and run the line these folks are running, walk it, take out above, or run the dangerous ledge. I’ll leave it up to you as to which of these options require someone to hang out with a rope.

Thanks to Matt Jackson for this photo, which clearly shows what I consider to be the primary hazard in Python.

Look, all of this takes extra time. It requires communication. It requires practice! Maybe you only feel it’s worthwhile to set two ropes. Or one! Or none. But please think about how to best approach it. We have way more tools and options at our disposal than we are taking advantage of. Bring a whistle. Bring a rope. Make a plan, and stick to it. Be patient. When in doubt scout! Watch your friends like a hawk. Speak up when you see something going on that could endanger someone. These rivers do not care. You have to make up the difference, and it takes extra effort - it’s worth it.

Thanks, peace to all reeling after the latest accident, and I hope to see you on the river whenever the time is right.

-Kirk